CONTINUED FROM PAGE ONE

7. OWN A VAN.

DEZ CADENA (third Black Flag vocalist, later guitarist): "When the Ramones first

came to L.A., we knew that they were a punk rock band, but because they were on

a big record label, we expected them to be in a big Winnebago and traveling like

rock stars. Instead they're coming out in this old beat-up '69 Ford van, with all

their equipment cramped together in the same vehicle. To us it was just very impressive.

Greg said that's why he decided he wanted to do everything on his own."

DUKOWSKI: "I bought this old '64 Ford Econoline window van, had it all slicked for

tours."

GINN: "When the tires would run too low, Chuck would get replacements from the ones

they throw out in the back of gas stations."

DUKOWSKI: "It was parked at my house, with 'Black Flag' and a million other band

names written all over it. I'd drive down the alley, and the Hermosa cops would

pull me over and just harass me. They'd leave me there and take my keys with them

back to the station, five or six blocks away. I'd have to walk to the station and

get my keys from them, then walk back up. Eventually, I took all the graffiti off

for this reason."

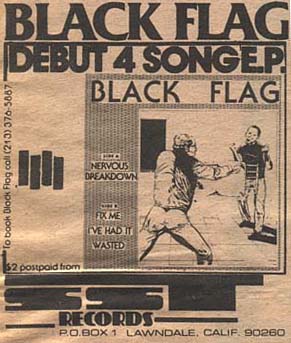

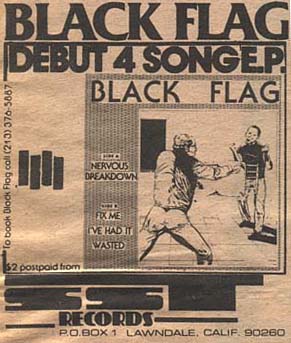

8. RELEASE YOUR OWN RECORD IF NO ONE ELSE WILL.

Egged on by a local African-American roller-skating-guitarist friend named Spot,

Black Flag (then called Panic) recorded eight songs in late-December '77 at

Media Art in Hermosa Beach. Bomp, a San Fernando Valley garage-rock label that

had expressed interest in releasing a Black Flag single, had been going through

cash-flow problems for more than six months. Around Christmas '78, Ginn pressed

up 2,000 copies of the four-song, five-minute Nervous Breakdown EP at a cost of

$1,000. The garish cover was by Pettibon, whose artwork and lettering would be

featured on almost all of Black Flag's releases, as well as those of other SST

artists like the Minutemen.

GINN: "We kept waiting and waiting for Bomp. Finally I decided to release it

myself, and that's where SST Records started. From SST Electronics, obviously

I knew how to set up a business. But I wasn't looking forward to putting out

records myself, because I felt that I had my hands full between working my

business and trying to play. So it was kind of by default: 'I can do this, so

I'll do it.'"

The band sold its records at shows and via mail orders to SST's P.O. box — an

address that never changed, despite the band having to move from city to city.

Sometimes the mail-order money was the band members' sole source of income. To

encourage retailers to order Black Flag records from the band's distributors,

band members would pose as fans and call stores across the country, requesting

the band's forthcoming record.

DUKOWSKI: "Brendan Mullen did us a favor. He gave us a phone-card number; someone

at U.S. Sprint had given it to him and said to have at it. He was in a good position

at U.S. Sprint — they were just starting out, no one was policing it. So we had

at it. I called everybody, all the time! I was on the phone from 9 in the morning

until 11 to 12 at night."

GINN: "Jem, which was an import distributor at the time, was the first real distribution

that we got. But retailers were used to marking up imports really high. We sold

our records real low to Jem, and then we'd go around to stores and they'd be in

'import' bins for way higher. So we felt like there wasn't proper distribution,

that we were dealing with people that were more interested in imports and it

just was not going to develop."

1981's Damaged would be Black Flag's highest-budget project ever, coming in at

around $8,000. Spot and the band produced it themselves. While recording the album,

Black Flag received an offer from a small label named Unicorn, which also owned

the Hollywood studio where the album was being cut. Unicorn had a distribution

deal with MCA. Hoping for better distribution than they had received so far,

Ginn and Dukowski decided to accept the offer. But just after 25,000 copies of

the album had been pressed, MCA distribution chief Al Bergamo announced that the

company would not distribute the record because, among other things, "It just

didn't seem to have any redeeming social value." With the MCA logo obscured by a

sticker quoting Bergamo ("As a parent with two children, I found it an anti-parent

record"), Damaged was eventually released by Unicorn through an independent distributor.

Later, after Unicorn's bankruptcy and almost two years of litigation (see Item No. 12),

the band re-released the album through SST.

1981's Damaged would be Black Flag's highest-budget project ever, coming in at

around $8,000. Spot and the band produced it themselves. While recording the album,

Black Flag received an offer from a small label named Unicorn, which also owned

the Hollywood studio where the album was being cut. Unicorn had a distribution

deal with MCA. Hoping for better distribution than they had received so far,

Ginn and Dukowski decided to accept the offer. But just after 25,000 copies of

the album had been pressed, MCA distribution chief Al Bergamo announced that the

company would not distribute the record because, among other things, "It just

didn't seem to have any redeeming social value." With the MCA logo obscured by a

sticker quoting Bergamo ("As a parent with two children, I found it an anti-parent

record"), Damaged was eventually released by Unicorn through an independent distributor.

Later, after Unicorn's bankruptcy and almost two years of litigation (see Item No. 12),

the band re-released the album through SST.

GINN: "We thought, 'MCA pretty much distributes Unicorn, and that's all they do.

And Unicorn was dealing with them, so I didn't have much contact with MCA. But I

guess someone at MCA heard it, and you know . . . There was just that kind of

cultural war: 'This is wrong.' The music business was just, 'We don't need this

punk culture.'"

9. LIVE COMMUNALLY.

For Penelope Spheeris' L.A. punk doc The Decline of Western Civilization, the band

was filmed inside its rehearsal space at a Hermosa Beach crafts center called the

Church. The band's then-singer, Ron Reyes, talked onscreen about how he was living

in the room's closet for $16 a month. By late '79, as Black Flag/SST became a

full-time occupation for its members, the band began to live together in its

various rehearsal/office spaces. For a period in August 1981, when the band was

homeless, SST's phones were the pay booths at the corner of Wilshire Boulevard

and Western Avenue, where Ginn and Dukowski spent whole days conducting SST/Black

Flag business.

DUKOWSKI: "It was a hard time for us. We were living on nothin'. We'd get some

mail-order money in the morning — if we were lucky — and go spend it."

CADENA: "We had this thing called 'good cop/bad cop.' Greg decided that Chuck

should take care of the money, because Greg was a little bit too nice. If you said,

'Greg, I need a little cash,' he'd go, 'Oh, here.' Whereas at times we had to be

tight-fisted to run this record company the way it needed to be run."

DUKOWSKI: "We'd sleep on the floor, wake up with the sun. Mr. Ginn [Greg's father]

would bring down a few sandwiches and feed us, pretty much every day. And he'd bring

us a load of clothes that he'd found at thrift stores."

GINN: "He would take these preppy shirts and put the four bars on them with a marker.

For tour, we'd have a bag of these clothes, and as the tour went on, you'd just go,

'Oh, I could use a new shirt' and pull one out of the bag . . . My parents went

through the Depression, they went through some really tough times, so they'd always

be thinking, 'Well, you gotta make sure you can survive the worst thing.'"

DUKOWSKI: "We'd be wearing old slacks and stuff from another era. It was like that

for roughly a year — grilled cheese sandwiches and piles of clothes. And pizzas.

It was all about cheese."

ROBO: "It was a hard life, but we all could do it because none of us were married.

As long as there was floor space to sleep on and a sandwich here and there, it

was okay with me. I had shitloads of fun playing, so I didn't care."

CADENA: "We would all have been miserable doing a 9-to-5 thing. We figured the only

way for us to do music would be to do it on our own. That also meant that we kind

of had to be like the Manson family and just all live together. But there was no

other way for these particular people to do it."

10. ADVERTISE.

In summer '81, Black Flag and Spot produced a series of radio commercials for

broadcast on KROQ, some of which made light of the punk rock scene's treatment

by the LAPD ("Attention all units! Chief Gates is in an uproar! Let's get those

punk rockers!") while publicizing their upcoming L.A.-area shows and their new

records.

DUKOWSKI: "I think it was Greg's idea: 'Let's do radio!' We'd just put our whole

crew together, people who were hanging around, mock up a script, and do it. That

was really the heyday of that stuff, when we were real fresh."

Ginn and Dukowski contend that Black Flag did not encourage or exploit the violence

that attended its shows, even as that violence — and the not-infrequent clashes

with police — inevitably drew media attention and gained the band free publicity.

DUKOWSKI: "We worked to try to create an environment where the right things could

happen, hopefully, and there was security and all of that in the venues. The violence

isn't a good thing — but on the other hand, what are you gonna do? One could say

if you go into a Raiders game and cheer for the Cowboys you're gonna get fucked

up. If you go to a Black Flag show and you' re wearing your Genesis T-shirt and

you're screaming, 'Punk rock is bunk squawk!' then you're gonna get yourself beat

up. Yes, the violence probably hurt us, but it's a two-sided coin. We can say we

could have been bigger without it, that without that stigma we would have been

allowed into the mainstream. On the other side of the coin, people were talking,

weren't they?"

GINN: "The news reports tied Black Flag and violence together, when that wasn't

at all appropriate. I thought, 'Well, you have more problems at some heavy-metal

show with a bunch of drunk people.' People thought it was great publicity, but

anytime you're misrepresented — unless you're trying to pull some kind of image

scam — it's gonna hurt you. We wanted to play music. We practiced five or six nights

a week to play, not to have our gigs stopped by the cops."

11. NEED A NEW SINGER? LOOK TO YOUR FANS.

When original Black Flag singer Keith Morris quit the band in '79, he was quickly

replaced by Ron Reyes, a Hermosa Beach teenager who had been following the band

since it was called Panic and knew all of the songs. Five months after Reyes quit

the band midshow, in '80, he was replaced by his 19-year-old friend (and longtime

Flag fan), guitarist Dez Cadena. Then, in late summer of '81, Cadena — whose

voice was faltering, and who was more interested in playing guitar, anyway — was

replaced on lead vocals by 20-year-old Washington, D.C., Flag fanatic Henry Rollins.

GINN: "Punk rock wasn't some kind of established thing. We all came from the audience.

Everybody in the band was always more of a rock fan than a rock star."

12. DO AS MUCH OF YOUR OWN LEGAL WORK AS POSSIBLE.

Black Flag's deal with Unicorn went sour, and the band soon found itself in court,

fighting to be released from a contract it claimed had been breached. A local lawyer

agreed to help the band in a supervisory role with their case.

GINN: "Our lawyer was like, 'You can't afford for our firm to do this, so you guys

do the work.' I'd taken legal-contract classes in college, so I was familiar with

the basics of law. Every day we'd take the bus from Redondo out to Hollywood and

Vine, where he was, and work on it. We did a lot of the legal filing, wrote a lot

of the motions, did a lot of research. We didn't end up paying him completely until

years after the band broke up. He was so good to us."

At one point, the band was enjoined from using the name Black Flag for any release,

even on recordings that had been made prior to entering a deal with Unicorn. After

releasing a double album, Everything Went Black, of early Black Flag recordings

without using the name Black Flag anywhere on the album, Ginn and Dukowski were

found in contempt of court. The judge sentenced them to five days each in L.A.

County Jail. Bill Stevenson, the band's new drummer, had been working with Ginn

and Dukowski on their case.

BILL STEVENSON: "I didn't visit them in jail. I was just at the law office, trying

to prepare this writ of habeas corpus to get 'em out of there. My take on it was

just to be proactive."

DUKOWSKI: "The appeal came through, after we'd served four and a half days...

Eventually Unicorn went bankrupt, and it just went away. They just got ground out

economically from all the paper we threw at 'em. It was an attrition thing — trench

warfare.

"You know, we barely stayed alive. All of these people in this teeny space... It

didn't take long before it started tearing at the seams of things. Too many people,

too little food, too little sleep — it fucked everybody up. We couldn't make money

on our records, and when we went on tour, we were touring on a several-year-old

record! It was annoying. Later on, I met one of the opponent law firm's legal

secretaries, and he said, 'You guys ran us ragged.' I was stoked to hear that."

One of the only BLACK FLAG fliers I've seen with Chavo pictured: March 1980 at San Francisco's Fab Mab

One of the only BLACK FLAG fliers I've seen with Chavo pictured: March 1980 at San Francisco's Fab Mab

The above article by Jay Babcock originally ran in the L.A. Weekly (June 22-28, 2001). Dixon Coulbourn

snapped the above live shot in Austin, Texas way back in 1982.

CONTACT: Break My Face

1981's Damaged would be Black Flag's highest-budget project ever, coming in at

around $8,000. Spot and the band produced it themselves. While recording the album,

Black Flag received an offer from a small label named Unicorn, which also owned

the Hollywood studio where the album was being cut. Unicorn had a distribution

deal with MCA. Hoping for better distribution than they had received so far,

Ginn and Dukowski decided to accept the offer. But just after 25,000 copies of

the album had been pressed, MCA distribution chief Al Bergamo announced that the

company would not distribute the record because, among other things, "It just

didn't seem to have any redeeming social value." With the MCA logo obscured by a

sticker quoting Bergamo ("As a parent with two children, I found it an anti-parent

record"), Damaged was eventually released by Unicorn through an independent distributor.

Later, after Unicorn's bankruptcy and almost two years of litigation (see Item No. 12),

the band re-released the album through SST.

1981's Damaged would be Black Flag's highest-budget project ever, coming in at

around $8,000. Spot and the band produced it themselves. While recording the album,

Black Flag received an offer from a small label named Unicorn, which also owned

the Hollywood studio where the album was being cut. Unicorn had a distribution

deal with MCA. Hoping for better distribution than they had received so far,

Ginn and Dukowski decided to accept the offer. But just after 25,000 copies of

the album had been pressed, MCA distribution chief Al Bergamo announced that the

company would not distribute the record because, among other things, "It just

didn't seem to have any redeeming social value." With the MCA logo obscured by a

sticker quoting Bergamo ("As a parent with two children, I found it an anti-parent

record"), Damaged was eventually released by Unicorn through an independent distributor.

Later, after Unicorn's bankruptcy and almost two years of litigation (see Item No. 12),

the band re-released the album through SST.

One of the only BLACK FLAG fliers I've seen with Chavo pictured: March 1980 at San Francisco's Fab Mab

One of the only BLACK FLAG fliers I've seen with Chavo pictured: March 1980 at San Francisco's Fab Mab