BLACK FLAG

A TWELVE-STEP PROGRAM IN SELF RELIANCE

HOW L.A.'s HARDCORE PIONEERS MADE IT THROUGH THE EARLY YEARS

by Jay Babcock

By midsummer 1981, when the then-unknown, now-notorious Henry Rollins joined Black

Flag as its fourth singer, the South Bay-based punk band had already tasted some

extremely hard-earned success. Despite a set of severe hurdles — from an initial

difficulty in getting local club gigs and a record deal to sensational "punk violence!"

coverage by the news media and constant harassment of both the band and its fans

by police — Black Flag had managed to self-release three EPs, tour North America

several times, and grow from playing to a couple of dozen people at a San Fernando

Valley coffeehouse to headlining shows at the Santa Monica Civic and Olympic

Auditorium.

Black Flag accomplished this by developing a do-it-yourself work and business

ethic which, although common in jazz, rhythm & blues and folk circles for decades,

was almost unique for American rock bands at the time. It was an ethic that was

hugely effective, and one that would prove hugely influential over the next two

decades.

But what's ironic about the band's current historical status as one of American

punk rock's original DIY pioneers — "They may well be the band that made the

biggest difference," says no less an authority than Fugazi's Ian MacKaye — is

that Black Flag's original aspirations had nothing to do with building an alternate

model to the existing music industry.

"The beginning and end of it was always working on the music," says Black Flag

founder, guitarist and chief songwriter Greg Ginn today. "The other stuff was

very much at the periphery."

As they tell it now, Ginn & Co. would have been quite content to let someone else

handle the mundane trivialities of being recording artists and performers: the nuts

and bolts of producing and releasing records, doing publicity and marketing, booking

tours, handling legal matters, lugging equipment, etc. Black Flag would play while

others would work. But the music industry, broadly speaking, wasn't interested in

Black Flag — so Black Flag had to figure out, almost on their own, how to get their

music heard. This is how they did it, in their own words:

1. PRACTICE HARD, ALL THE TIME.

GREG GINN: "For us, it was all about practice, and always playing. A lot of times

we didn't have a place to live, but we always paid for a place to practice hours

every day, through the whole Black Flag history. If we were living in vans, living

in the practice place or staying with people or whatever, we always had a place

to practice."

KEITH MORRIS (first Black Flag vocalist): "We got totally fed up with our original

rhythm section. It got to the point where they were so flaky that we weren't even

rehearsing. We'd started to get our work ethic going, but it didn't hit fifth gear

until we got Robo and Chuck the Duke [Dukowski] in the band. And then it was like

we rehearsed every night, sometimes for six hours. Sometimes I wouldn't be getting

home until, like, 4 in the morning."

GINN: "I thought that if you're gonna call yourself a band and claim to play music,

it's not too much to ask that you practice a couple hours, five nights a week.

But a lot of people thought, 'Well, we'd rather party or hang out or this or that.'

And punk rock, there was a lot of that mentality — 'Why do you need to practice

so much?' It was supposed to be 'Everything's zero, and life's not worth anything,

so why would you bother practicing?' I' m not saying that my attitude is right.

Other bands were different. Like the Germs — they didn't practice, and I loved

to go see them play. I wouldn't have tried to change them! I was just, 'Okay,

that's them. We're not the Germs. We're doing something different.'"

2. HAVE EXPERIENCE RUNNING A SMALL BUSINESS.

Ginn, who graduated from UCLA with an economics degree, started his first business

— SST Electronics — when he was in junior high school, and continued to run it

through college and into his 20s. SST provided friends with work — Morris, Dukowski

and Mike Watt (among others) all made antenna tuners or other ham-radio accessories

at some point — and generated the seed money Ginn used to fund Black Flag's early

activities.

MORRIS: "Greg was basically our financier — he was our industrial capitalist."

While he was at UC Santa Barbara, Chuck Dukowski ran a production company that put

on shows and movies. He'd also "toured" the U.S. in a van twice, playing rock gigs

with a high school friend in a band that eventually became Würm.

DUKOWSKI (bass): "We had a single 12-inch speaker, we'd both plug into it, and

we'd go and jam everywhere. After college, we rented a bunch of different storefronts

and commercial spaces that we'd live in and practice in, and try to get the ball

rolling with our band. Eventually, we ended up in a deserted bathhouse and

restaurant in Hermosa Beach. We bought and sold musical equipment to make money.

Würm couldn't get gigs, so we played to 20 to 30 people a night, pretty much seven

days a week, at our pad. We had it all organized — how to stay underground and

avoid getting into trouble. We even had a secret knock."

After Würm fell apart, Dukowski joined Black Flag (then called Panic) and took

a day job as a foreman at a local pool-table manufacturing company.

DUKOWSKI: "[In late '79] I was just sitting around at this job, being the foreman,

and I smelled the solvents floating in the air, and I went, 'This isn't good for

me. I want to go into music, that's what I've been wanting to do all along.' And

I'd seen that this guy built this pool-table place from nothing, and I had some

experience in entertainment, and I had experience with touring — not as a band,

but traveling and being self-sustaining on the road for months at a time. So I

quit, and my primary focus became SST. Greg had invited me to be a partner at the

label. I walked in, I said, 'Okay, I got time and energy, I wanna make it work.

We got a little bit of time to set it up, because soon enough my savings will

run out.'"

3. DO YOUR OWN PUBLICITY.

(a) GRAFFITI

One of Greg Ginn's younger brothers was Raymond Pettibon, an artist who specialized

in chilly one-panel comic-book-style drawings with unsettling captions. Pettibon

came up with the name Black Flag, as well as the band's logo and its marvelously

simple emblem: an unfurled flag broken in three so that it appeared as four solid

vertical black bars. The "four bars" was perfect for graffiti.

MORRIS: "Aw, we had graffiti everywhere — freeway overhangs, underpasses. We were

probably the original L.A. taggers."

ROBO (drums): "Greg's girlfriend Medea used to go to Hollywood with a spray can,

and every wall that she saw, she put up the four bars. The police were like,

'Who the fuck is doing all this four bars everywhere?'"

GINN: "In the South Bay, the band was known for its graffiti. It was so uncommon

that when you did it, everybody saw it. That was the one outlet that we had to

publicize the group. Which I think is totally justifiable in light of the cartel

in music that the big record labels had going — and still have, to a certain extent.

If people don't have a voice at all, if the government is supposed to support

free enterprise but they're supporting these really close-knit cartels, then the

people need to make some kind of noise to start breaking that stuff up."

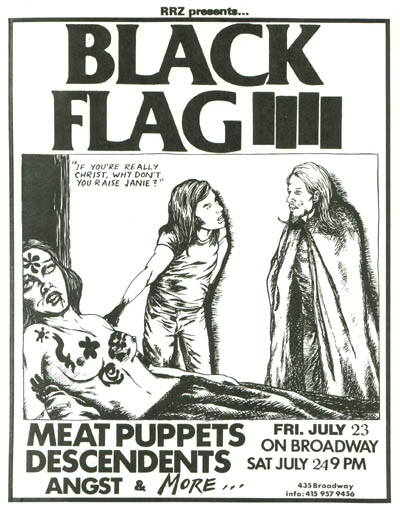

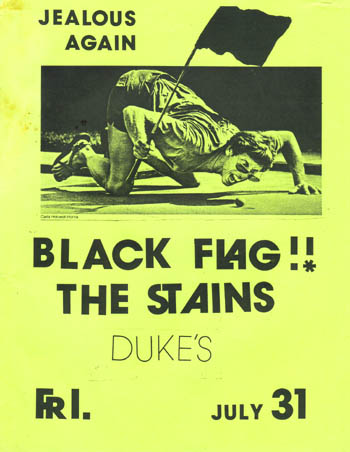

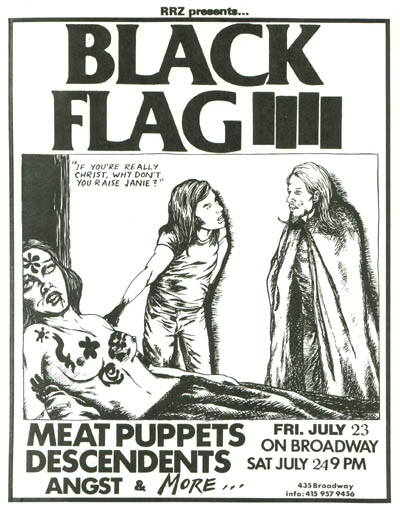

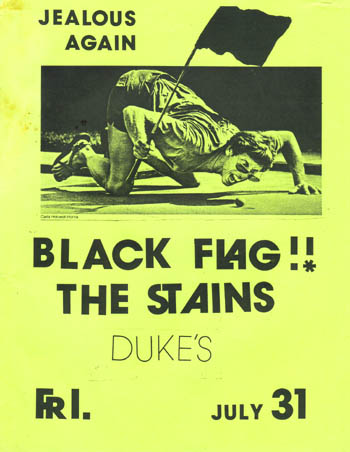

(b) FLIERS

Pettibon's artwork was also featured on almost all of Black Flag's fliers

advertising upcoming gigs. The posters for a series of late-1980 shows around

L.A. that had been nicknamed "creepy crawls" (after a term used by the Manson

family for breaking into people's houses and rearranging their furniture) are

particularly intense. One features a blond girl warning an X-carved-between-the-eyebrows

Charles Manson ("You better be good, Charlie. It wasn't easy getting in here you know").

The fliers' content — and their ubiquity on telephone poles and street walls —

contributed to the band's already edgy, menacing mystique.

MORRIS: "We would go out on our flier-pasting missions in Robo's little white Ford

Cortina. We'd have the bucket with the paste, we'd have a few hundred fliers, and

after all the fliers were posted, like three or four hours, we'd go home and go

to sleep."

DUKOWSKI: "The minimum that went out was 500 for a show. I made a wheat-paste/white-glue

mix so that it would stay up longer. Nobody did that. When I was producing shows in

college, I realized you need to plaster this shit — you need to put 30 of them here,

and they need to be put up so they' re there for a while. The Dogs and other people

had been doing it, but they could have been more aggressive — they weren't putting

them up on poles. That helped us get over, for sure . . . For one of those early

shows, we put fliers somewhere, and Greg had to go to court for it. And they fined

him or something. Our response to that was to go right from the courthouse to the

Redondo Beach police station and graffiti the station wall in broad daylight."

4. GET LOCAL GIGS.

Unable to get a show anywhere, the band decided to book a late-January '79 afternoon

at a Moose Lodge in Redondo Beach and put on a show itself. The event drew less than

100 people, but included two of the band's future singers — and an impressed Rodney

Bingenheimer, who began playing the band's first single immediately after.

GINN: "There was an underground of rock bands in L.A. in '74, '75 — before punk rock.

The Alleycats, the Last, the Dogs, the New Order. Those bands were playing outside

of the put-on-a-stage-show, wear-costumes, showcase-for-the-label thing. They'd

rent halls, do fliers. They would just keep plugging away, to very limited success.

I really picked up on the kind of work ethic those bands had."

DUKOWSKI: "Greg organized most of the bookings at first. We played a lot of local

clubs, but it was more catch-as-catch-can kind of stuff. One advantage Black Flag

had was there was a place where we could be reached, 'cause he had a business

phone for SST Electronics."

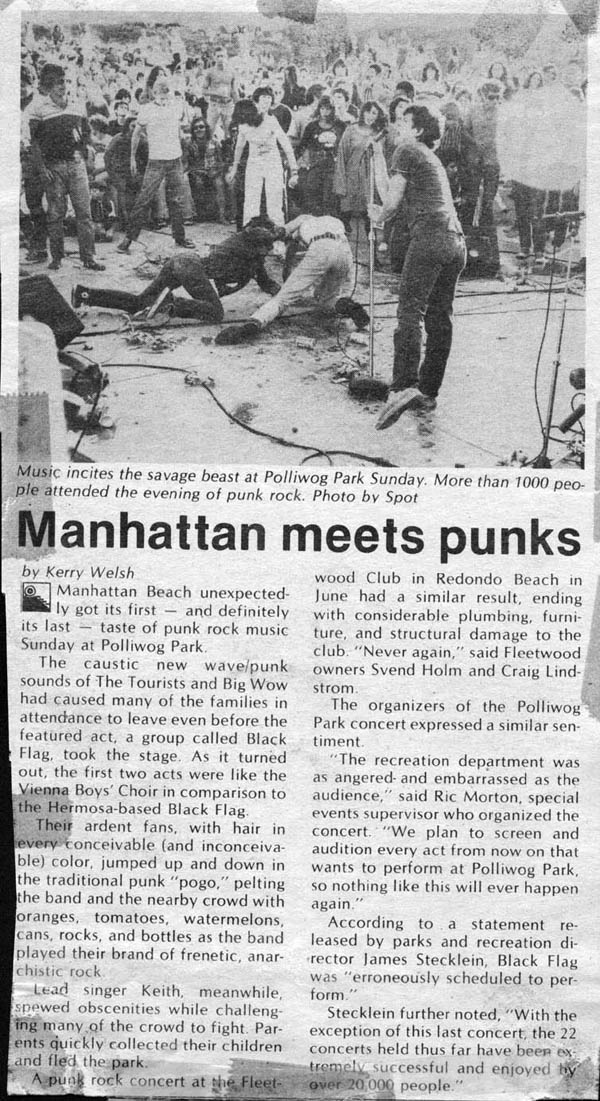

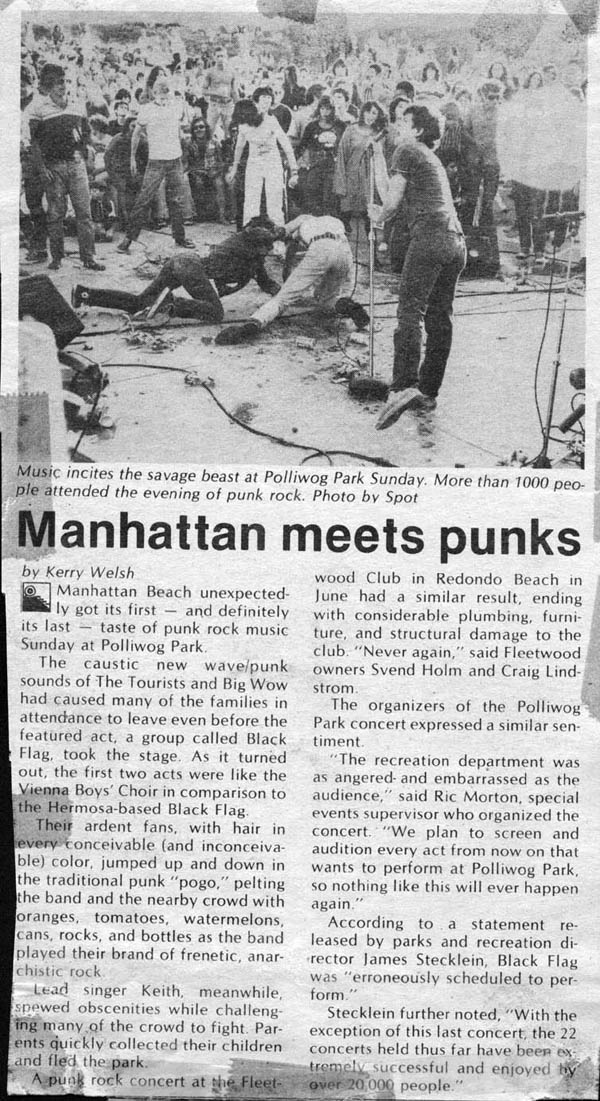

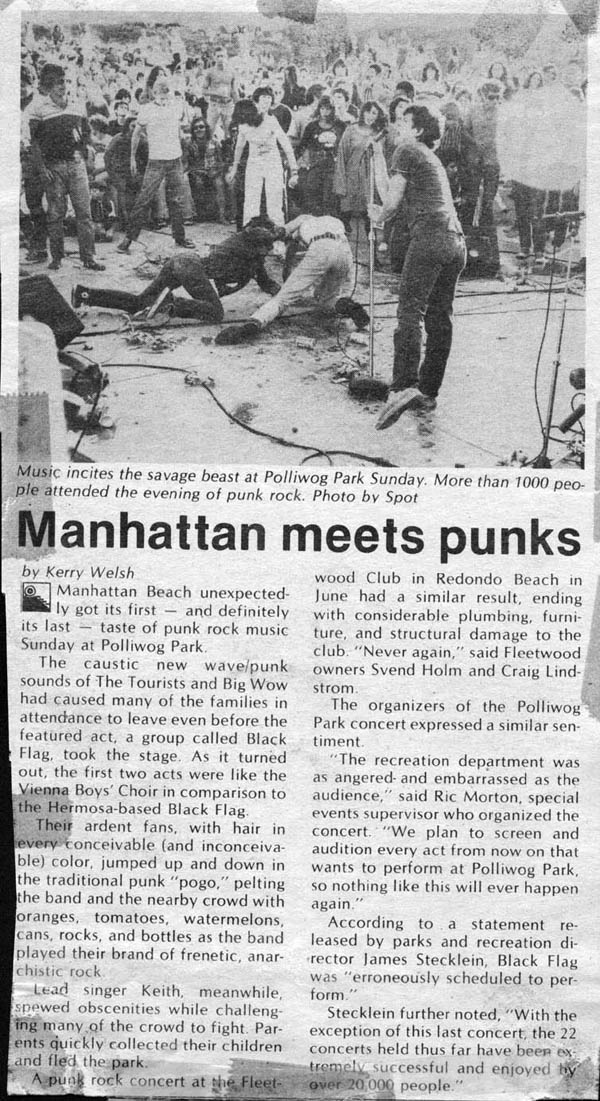

Black Flag began making a name for itself in the Hollywood scene by playing a series

of gigs at local clubs that summer. Then, somehow, Ginn got Black Flag on the bill

for a free Sunday-afternoon concert at Polliwog Park in Manhattan Beach. The band's

set was accompanied by a barrage of lunch food thrown at the band — and its few fans

— by the disapproving audience of picnicking families. Black Flag's first gigs at

other unconventional venues were also usually their last.

GINN: "I got real good at talking to promoters or hall owners. They'd ask, 'What

kind of music do you play?' I'd say, 'Oh, it's a rock group and a little bit of

jazz in there.' That's a trick — the 'jazz' word is always useful when you're

stopped by police or authorities. 'What kind of music do you guys play?' If you

answer 'rock,' they ask, 'What kind of rock?' But if you throw that little 'jazz'

thing in there . . ."

DUKOWSKI: "Once I had the time and energy to put into booking the band's shows,

we started putting together packages to attract audiences from different parts

of the city. We'd say, 'Okay, we're gonna have a group from here, a group from

there, bring it all together and promote the hell out of it. We get these people's

audiences plus a few new people each time.' And it worked."

GINN: "We didn't turn down any free gigs, because those were the best. It'd cost

us money, because we'd rent PAs, but I always liked free gigs because anybody

can wander in. You could get different people at random, not pre-selected groups

of people, and maybe they would get something out of it. That's how I got into

music, through free stuff . . ."

5. TOUR.

After playing dates up and down the West Coast several times, in December 1980

the band embarked on its first national tour, booking shows with often unknown

promoters at often questionable venues on hearsay information passed to them

by other touring punk bands like San Francisco's Dead Kennedys, Vancouver's

D.O.A. and Texas' Big Boys. Black Flag toured the U.S. three times in nine months

spanning '80-'81.

DUKOWSKI: "We needed to work, to keep the ball rolling. Especially if you're only

making 50 bucks, 100 bucks, something like that, every time you do it. We needed

to play every night. And the only way to play a show every night was to tour."

GINN: "We tried to book a show every day, and then cancellations would be days off.

And as we went, we could fill it in more. There's no way we could have done the

same thing [using normal music-business procedures and personnel], because who's

gonna book tours so they can take their 15-percent share for a show where we made

$50? Who's gonna go along with it and do all the work and say, 'We play any live

gig, we put parties ahead of paying things'? That's what we did for our whole career.

You have to take yourself outside of the regular business, because no manager or

label is gonna have the foresight to do all of that stuff to create something

bigger, because they can't see their interest beyond the short term."

ROBO: "We set up our own instruments, we only had one roadie, which was a teenage

street kid nicknamed Mugger. I'd carry my drums in all by myself, Greg carried,

and Chuck carried in his cabinets. We all did it ourselves. No bullshit. We only

wanted a bright white light on us, so we could see each other and people could

see us. None of this bullshit of fog and smoke and dimmed lights. If there's a

drum riser on the stage, get it off! We want a carpet and a white light. We don't

need nothing else!"

6. WATCH YOUR DIET.

DUKOWSKI: "Ron Reyes [the band's second singer] had next to no money and was living

on potatoes. Which is a pretty good choice of food to live on. But on the other

hand, he was living too hard — he was drinking a lot — and tried to be a vegetarian

too. Not having enough money to eat right, that's a good way to get malnourished.

He freaked out."

ROBO: "I sweat like a pig from the way I play. I really put out. So, playing so

much, I lost a lot of weight. I'd been a vegetarian for like seven or eight years.

I said, 'Man, I'm gonna either drop dead or get sick.' So I started eating meat

again."

CONTINUED ON PAGE TWO

CONTACT: Break My Face

![]()

![]()

![]()